Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) occurs when there is an abnormal increase in the overall bacterial population in the small intestine. In a healthy digestive system, the vast majority of gut bacteria reside in the large intestine (colon), while the small intestine is relatively sterile to allow for the absorption of nutrients. When bacteria migrate upwards or multiply excessively in the small bowel, they begin fermenting food prematurely, leading to a host of uncomfortable digestive symptoms and potential nutrient deficiencies.

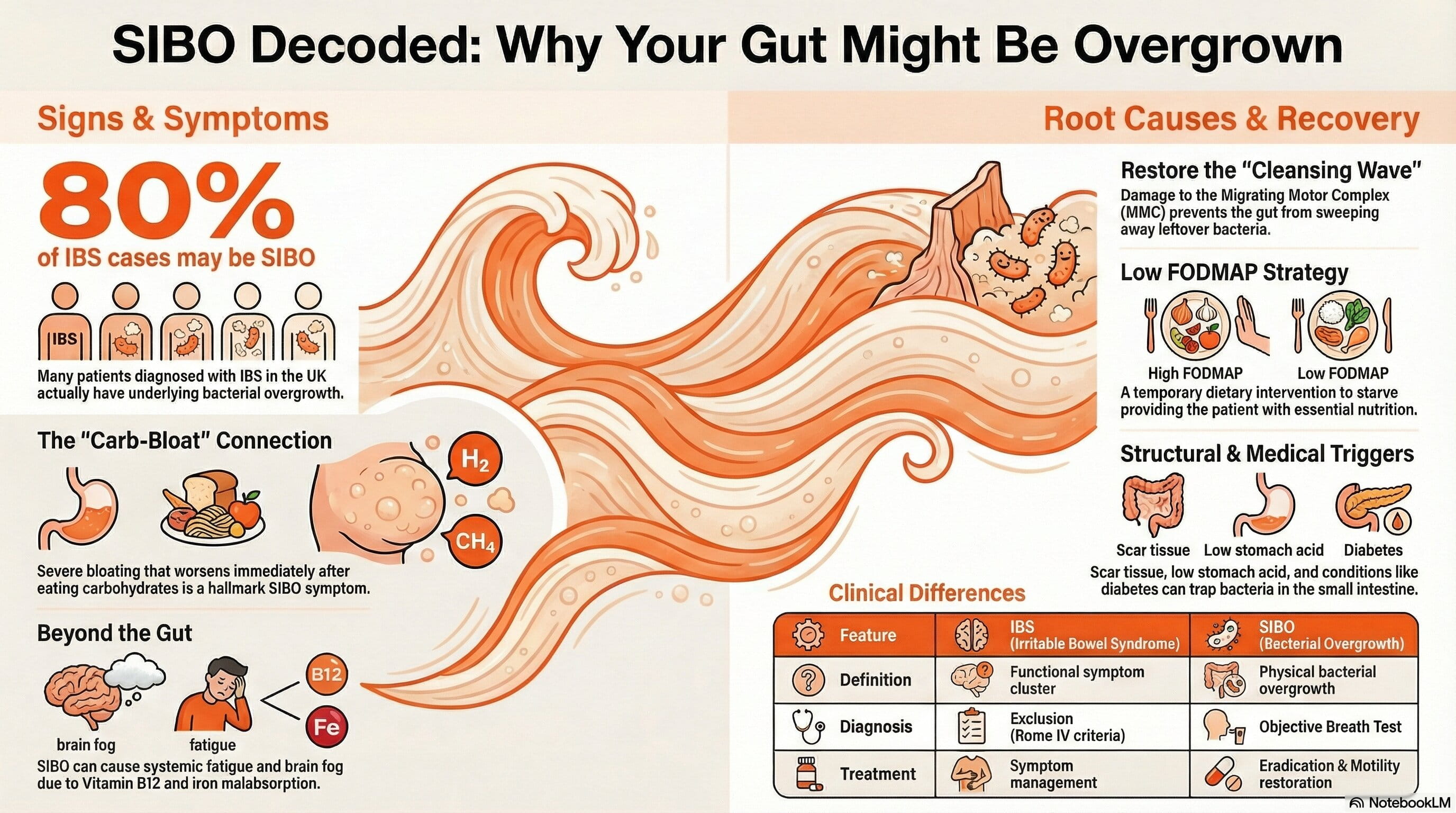

Common Symptoms of Bacterial Overgrowth

The hallmark symptom of SIBO is severe abdominal bloating that typically worsens as the day progresses or immediately after eating carbohydrates. Because the misplaced bacteria feed on the food you digest, they produce large amounts of gas as a byproduct. This process triggers several noticeable signs:

- Excessive flatulence and belching: Caused by the build-up of hydrogen, methane, or hydrogen sulphide gases.

- Altered bowel habits: Depending on the type of gas produced, patients may experience chronic diarrhoea, stubborn constipation, or alternating patterns of both.

- Abdominal pain and cramping: The physical stretching of the intestinal walls from trapped gas causes significant discomfort.

- Fatigue and brain fog: Systemic inflammation and the malabsorption of vital nutrients like Vitamin B12 and iron can leave you feeling drained.

What Causes SIBO?

SIBO is rarely a standalone condition and is almost always caused by an underlying structural or functional issue that disrupts the gut's natural clearing process. The body has several defence mechanisms to keep the small intestine clear, and SIBO develops when one or more of these mechanisms fail.

Impaired Migrating Motor Complex (MMC)

The most common functional cause of SIBO is a damaged Migrating Motor Complex, which is the mechanical "cleansing wave" that sweeps leftover food and bacteria through the digestive tract between meals. If you have suffered from food poisoning or gastroenteritis, the resulting nerve damage can slow down this vital wave [1], allowing bacteria to stagnate and multiply.

Structural and Medical Factors

Physical blockages or changes to the gut anatomy can also trap bacteria. This includes scar tissue from previous abdominal surgeries, a malfunctioning ileocecal valve (the doorway between the small and large intestine), or conditions that slow digestion like hypothyroidism and diabetes. Furthermore, the long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) lowers stomach acid [2], removing a primary barrier that normally kills ingested bacteria.

SIBO vs. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

SIBO is frequently misdiagnosed as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) because the symptoms are nearly identical. In fact, clinical data suggests that up to 80% of patients diagnosed with IBS in the UK may actually have underlying SIBO [3]. The table below outlines the relationship between the two conditions.

| Feature | IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) | SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A functional disorder categorised by a cluster of symptoms (pain, altered bowels) without visible disease. | A measurable, physical overgrowth of bacteria in the wrong part of the digestive tract. |

| Diagnosis Method | Diagnosed by exclusion using symptom criteria (Rome IV criteria). | Diagnosed objectively via a medical breath test or fluid aspirate. |

| Treatment Approach | Often focuses on symptom management (antispasmodics, stress reduction, dietary changes). | Focuses on eradicating the overgrowth (antibiotics or herbal antimicrobials) and restoring gut motility. |

How SIBO is Diagnosed

SIBO is usually diagnosed using a non-invasive lactulose or glucose breath test prescribed by a GP or a gastroenterologist. After drinking a sugar solution, the patient breathes into a series of tubes over two to three hours. Because humans do not exhale hydrogen or methane naturally, elevated levels of these gases in the breath indicate that bacteria in the small intestine are fermenting the sugar early [4].

Dietary and Medical Management

Managing SIBO requires a multi-step approach that involves clearing the overgrowth, repairing the gut lining, and preventing relapse. Medical treatments often involve specific, non-absorbable antibiotics like Rifaximin [5], which stay localised in the gut.

From a nutritional standpoint, the goal is to temporarily starve the bacteria while feeding the patient. The most evidence-based dietary intervention is the Low FODMAP diet [6]. FODMAPs are specific types of fermentable carbohydrates found in foods like onions, garlic, apples, and wheat. By restricting these highly fermentable foods for a short period, patients can drastically reduce gas production and relieve symptoms. It is highly recommended to undertake this diet under the supervision of a registered dietitian to ensure nutritional needs are met.

Nutritionist's Corner: Final Thoughts

"SIBO is a complex condition that requires a root-cause approach, as simply treating the overgrowth without fixing why it happened will almost certainly lead to a relapse. Diet plays a massive role in symptom management, but it is crucial to remember that restrictive diets like Low FODMAP are a short-term tool, not a life sentence. The ultimate goal of any SIBO protocol is to eradicate the misplaced bacteria, stimulate the gut's natural cleansing waves by spacing out meals, and eventually reintroduce a diverse range of plant fibres to rebuild a resilient, healthy microbiome in the large intestine where it belongs."

Yusra Serdaroglu Aydin, MSc RD

Sources

Author

Yusra Serdaroglu Aydin, MSc RD

Head of Nutrition and Registered Dietitian

Yusra is a registered dietitian with a multidisciplinary background in nutrition, food engineering, and culinary arts. During her education, her curio...